Application of Derivatives

Imagine you are driving a car and want to know how fast you are moving at a particular instant, not just the total distance you have covered. The concept of finding an instantaneous rate of change forms the foundation of the Applications of Derivatives. In Class 12 Mathematics, this chapter explains how derivatives are used beyond formulas to study real-life situations involving change. The Application of Derivatives deals with the practical use of differentiation to analyse the behaviour of functions. It helps us determine whether a function is increasing or decreasing, find points of maximum and minimum values, calculate rates of change, and draw tangents and normals to curves. For example, engineers use derivatives to find the maximum strength of a structure, economists use them to analyse profit and loss, and scientists use them to study speed, acceleration, and growth rates.

This Story also Contains

- Application of Derivatives in Mathematics

- Monotonicity (Increasing and decreasing functions)

- Application of Derivatives Formulas

- Important Formulae for Application of Derivatives

- Application Of Derivatives in Mathematics: Solved Previous Year Questions

- Applications of Derivatives in Different Exams

- List of topics related to the Application of Derivatives according to NCERT/JEE Mains

- Important Books and Resources for the Application of Derivatives

- NCERT Resources for Application of Derivatives

- NCERT Subjectwise Resources

- Practice Questions based on Applications of Derivatives

- Conclusion

In Class 12 Application of Derivatives, students learn important concepts such as rate of change, monotonic functions, tangents and normals, and maxima and minima. This chapter is highly scoring and forms an essential part of board exams and competitive exams such as JEE and NEET. In this article, you will find application of derivatives formulas, clear explanations, solved examples, and Class 12 application of derivatives important questions to help you understand how derivatives are applied in mathematics and everyday life.

Application of Derivatives in Mathematics

Application of Derivatives helps us understand how quantities change with respect to one another in real situations. It is used to study increasing and decreasing functions, find maximum and minimum values, and analyse rates of change in mathematical problems.

Application of Derivatives

Derivatives are used to find the rate of change of a quantity. Derivatives have numerous applications, such as calculating velocity, predicting sales over time, forecasting bacterial growth, and the spread of infection, among others.

The application of derivatives is mainly around the concepts of rate of change of quantities, approximation, tangent and normal to a curve, increasing and decreasing functions and minima and maxima of the function. Before looking in detail at this topic, let us recall what a derivative is.

Rate of Change

The value obtained after differentiating a function is called the derivative.

If two related quantities are changing over time, the rates at which the quantities change are related. For example, consider a balloon with air; both the radius and the volume of the balloon increase as the air in it increases.

If a variable quantity $y$ depends on and varies with a quantity $x$, then the rate of change of $y$ with $x$ is $\frac{d y}{d x}$.

For example, the rate of change of displacement ($s$) of an object w.r.t. time ($t$) is velocity $(\mathrm{v})$.

$v=\frac{d s}{d t}$

Let us consider the stone being thrown at a lake, causing circular waves at a speed of 4cm per second. Now, let us find how fast the enclosed area increases.

The area of a circle with radius $r$ is given by $\mathrm{A}=\pi r^2$. Therefore, the rate of change of area with respect to time $t$ is

$

\frac{d \mathrm{~A}}{d t}=\frac{d}{d t}\left(\pi r^2\right)=\frac{d}{d r}\left(\pi r^2\right) \cdot \frac{d r}{d t}=2 \pi r \frac{d r}{d t}

$

As the waves move at a speed of 4cm,

$

\frac{d r}{d t}=4 \mathrm{~cm} / \mathrm{s}

$

$\frac{d \mathrm{~A}}{d t}=2 \pi(10)(4)=80 \pi$

Thus, the enclosed area is increasing at the rate of $80 \pi \mathrm{~cm}^2 / \mathrm{s}$, when $r=10 \mathrm{~cm}$.

Linear Approximation

Linear approximation is used to estimate the value of the function close to the chosen point.

Let $f:(a, b) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be a differentiable function and $x_0 \in(a, b)$. We define the linear approximation $L$ of $f$ at $x_0$ by

$

L(x)=f\left(x_0\right)+f^{\prime}\left(x_0\right)\left(x-x_0\right), \quad \forall x \in(a, b)

$

For instance, let us assume that the shape of a soap bubble is a sphere. Now, let us approximate the increase in the surface area of a soap bubble as its radius increases from 5 cm to 5.2 cm.

The surface area of the soap bubble with radius $r$ is $S(r)=4 \pi r^2$.

$S'(r) = 8 \pi r$

Change in the surface area

$

\begin{aligned}

S(5.2)-S(5) & \approx S^{\prime}(5)(5.2-5) \\

& =8 \pi(5)(0.2)=8 \pi \mathrm{~cm}^2

\end{aligned}

$

Now, let us look into the types of errors.

Absolute Error

$\Delta \mathrm{x}$ or $d x$ is called absolute error in $x$.

Relative Error

$\frac{\Delta \mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{x}}$ or $\frac{d x}{\mathrm{x}}$ is called the relative error in $x$

Percentage Error

$\frac{\Delta \mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{x}} \cdot 100$ or $\frac{d x}{\mathrm{x}} \cdot 100$ is called the percentage error in $x$.

Tangent and Normal to a Curve

A tangent is a line touching the curve at only one point without passing through it. The tangent to a curve at a point P on it is defined as the limiting position of the secant $P Q$ as the point $Q$ approaches the point $P$ provided such a limiting position exists. The slope and equation of the tangent can be found with the use of derivatives if the curve of the function is given.

Let $P\left(x_0, y_0\right)$ be a point on the continuous curve $y=f(x)$, then the slope of the tangent to the curve at point $P$ is

$

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x_0, y_0\right)} \\

& \Rightarrow\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x_0, y_0\right)}=\tan \theta=\text { slope of tangent at } P

\end{aligned}

$

Where $\theta$ is the angle which the tangent at $\mathrm{P}\left(\mathrm{x}_0, \mathrm{y}_0\right)$ makes with the positive direction of the $x$-axis, as shown in the figure.

-

If the tangent is parallel to the $x$-axis, then $\theta=0^{\circ}$.

$

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \tan \theta=0 \\

& \therefore \quad\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x_0, y_0\right)}=0

\end{aligned}

$ -

If the tangent is perpendicular to $x$-axis then $\Theta=90^{\circ}$

$

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \tan \theta \rightarrow \infty \quad \text { or } \quad \cot \theta=0 \\

& \therefore\left(\frac{d x}{d y}\right)_{\left(x_0, y_0\right)}=0

\end{aligned}

$

Equation of Tangent

Let the equation of the curve be $y=f(x)$ and let point $P\left(x_0, y_0\right)$ lie on this curve.

The slope of the tangent to the curve at a point $P$ is $

\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x_0, y_0\right)}

$

Hence, the equation of the tangent at point $P$ is $

\left(y-y_0\right)=\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x 0, y_0\right)} \cdot\left(x-x_0\right)

$

Equation of Normal

The equation of normal of a curve is $\left(y-y_0\right) f^{\prime}\left(x_0\right)+\left(x-x_0\right)=0$.

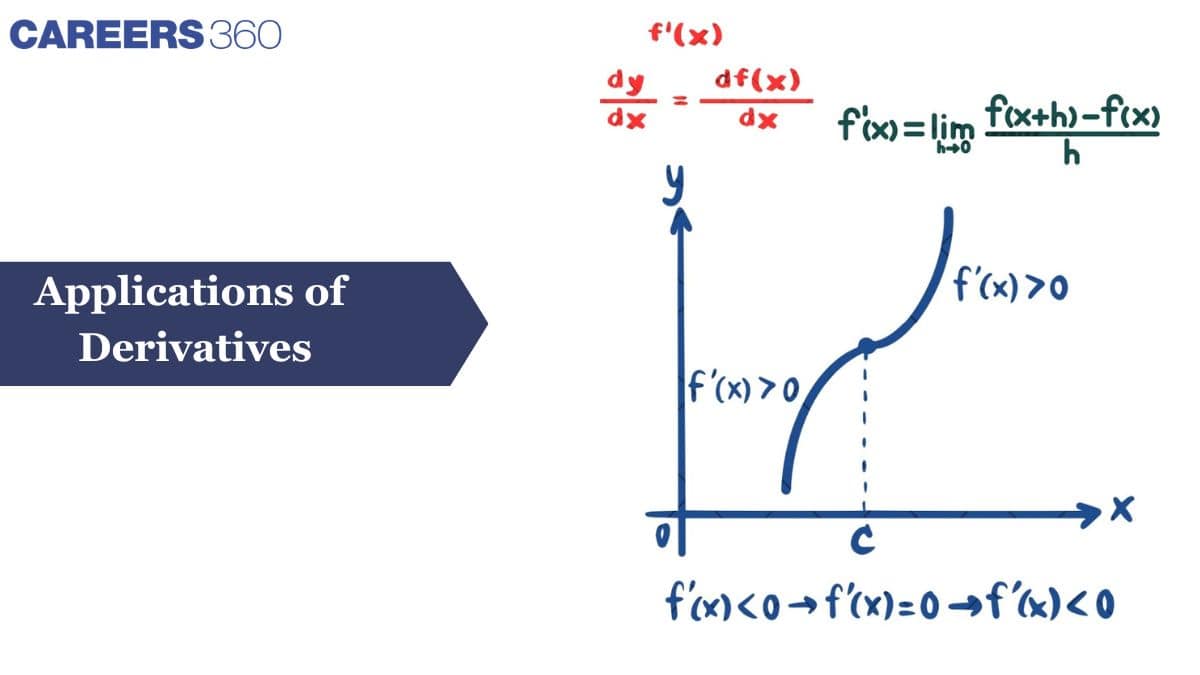

Monotonicity (Increasing and decreasing functions)

Monotonicity is the behaviour of the function, whether it is increasing or decreasing. A function is said to be monotonic if it is either increasing or decreasing in its entire domain. The behaviour of the function is determined using the concept of derivatives.

Increasing and Decreasing Functions: Application of Derivatives Class 12

A function is said to be an increasing function if it increases throughout its domain. A function $f(x)$ is increasing in the interval $[a, b]$ if $f(x_2) \geq f(x_1)$ for all $x_2 > x_1$, where $x_1, x_2 \in [a, b]$. If the function is differentiable, then $\frac{d}{dx}f(x) \geq 0 \quad \forall x \in (a, b)$ represents an increasing function, while $\frac{d}{dx}f(x) > 0 \quad \forall x \in (a, b)$ represents a strictly increasing function.

A function is said to be a decreasing function if it decreases throughout its domain. A function $f(x)$ is decreasing in the interval $[a, b]$ if $f(x_2) \leq f(x_1)$ for all $x_2 > x_1$, where $x_1, x_2 \in [a, b]$. If the function is differentiable, then $\frac{d}{dx}f(x) \leq 0 \quad \forall x \in (a, b)$ represents a decreasing function, while $\frac{d}{dx}f(x) < 0 \quad \forall x \in (a, b)$ represents a strictly decreasing function.

Examples of Increasing and Decreasing Functions

For example, consider the function $f(x) = x$. Its derivative $f'(x) = 1 > 0$, which means $f(x)$ is an increasing function. Similarly, for $f(x) = -x$, we have $f'(x) = -1 < 0$, making it a decreasing function.

Application of Derivatives in Monotonicity

One of the main applications of derivatives class 12 is the study of monotonicity. By analysing the derivative of a function, we can determine where the function is increasing or decreasing. This has practical real-life applications, such as finding the increase or decrease in profit, sales, production, or cost. Understanding these trends is crucial in fields like economics, business, and engineering.

Behaviour of the function due to Monotonicity

-

$f'(x) > 0 \implies$ Function is strictly increasing

-

$f'(x) \ge 0 \implies$ Function is increasing

-

$f'(x) < 0 \implies$ Function is strictly decreasing

-

$f'(x) \le 0 \implies$ Function is decreasing

Using these applications of derivatives class 12 solutions and formulas, students can solve various problems related to real-world scenarios involving growth and decline effectively.

Maxima and Minima

The maximum and minimum values of a curve can be determined using derivatives.

Let $f$ be a function defined on an open interval $I$. Let $f$ be continuous at a critical point $c$ in $I$. Then

(i) If $f^{\prime}(x)$ changes sign from positive to negative as $x$ increases through $c$, i.e., if $f^{\prime}(x)>0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the left of $c$, and $f^{\prime}(x)<0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the right of $c$, then $c$ is a point of local maxima.

(ii) If $f^{\prime}(x)$ changes sign from negative to positive as $x$ increases through $c$, i.e., if $f^{\prime}(x)<0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the left of $c$, and $f^{\prime}(x)>0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the right of $c$, then $c$ is a point of local minima.

Let $y=f(x)$ be a real function defined at $x=a$. Then the function $f(x)$ is said to have a maximum value at $x=a$ if $f(x) \leq f(a) \quad \forall a \in$ R.

And also the function $f(x)$ is said to have a minimum value at $x= a$, if $f(x) \geq f(a) \quad \forall a \in R$

If at $x=a$ the shape of the curve changes from increasing to decreasing or from decreasing to increasing. Then $\mathrm{x}=\mathrm{a}$ is known as the point of inflection and $f^{\prime \prime}(x)=0$ at $x=a$

These maximum and minimum values have a lot of applications in real-life problems. It can be used to determine the maximum profit, to determine the dosage of a medicine, etc.

Now, let us summarise and recall the application of derivative formulas.

Application of Derivatives Formulas

The application of derivatives formulas includes the formulas of rate of change, approximation and errors, equation of tangent and normal to the curve, conditions for increasing and decreasing functions, and maxima and minima.

Rate of Change

If two related quantities are changing over time, the rates at which the quantities change are related. If a variable quantity $y$ depends on and varies with a quantity $x$, then the rate of change of $y$ with $x$ is $\frac{d y}{d x} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}$.

Linear Approximation and Error

Linear approximation is used to estimate the value of the function close to the chosen point.

Let $f:(a, b) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be a differentiable function and $x_0 \in(a, b)$. We define the linear approximation $L$ of $f$ at $x_0$ by

$

L(x)=f\left(x_0\right)+f^{\prime}\left(x_0\right)\left(x-x_0\right), \quad \forall x \in(a, b)

$

Tangent and Normal to a Curve

The equation of a tangent to a curve at point $P$ is $

\left(y-y_0\right)=\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x 0, y_0\right)} \cdot\left(x-x_0\right)

$ where $\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)_{\left(x 0, y_0\right)}$ is the slope.

The equation of normal of a curve is $\left(y-y_0\right) f^{\prime}\left(x_0\right)+\left(x-x_0\right)=0$.

Monotonicity (Increasing and decreasing functions)

A function $f(x)$ is increasing in $[a, b]$ if $f\left(x_2\right) \geq f\left(x_1\right)$ for all $x_2>x_1$, where $x_1, x_2 \in[a, b]$. If a function is differentiable, then $\frac{d}{d x}(f(x)) \geq 0 \quad \forall x \in(a, b)$ is a increasing function while $\frac{d}{d x}(f(x)) > 0 \quad \forall x \in(a, b)$ is a strictly increasing function.

A function $f(x)$ is decreasing in the interval $[a, b]$ if $f\left(x_2\right) \leq f\left(x_1\right)$ for all $x_2>x_1$, where $x_1, x_2 \in[a, b]$. If a function is differentiable, then $\frac{d}{d x}(f(x)) \leq 0 \quad \forall x \in(a, b)$ is a decreasing function while $\frac{d}{d x}(f(x)) < 0 \quad \forall x \in(a, b)$ is a strictly decreasing function.

Maxima and Minima

If $f^{\prime}(x)$ changes sign from positive to negative as $x$ increases through $c$, i.e., if $f^{\prime}(x)>0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the left of $c$, and $f^{\prime}(x)<0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the right of $c$, then $c$ is a point of local maxima.

If $f^{\prime}(x)$ changes sign from negative to positive as $x$ increases through $c$, i.e., if $f^{\prime}(x)<0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the left of $c$, and $f^{\prime}(x)>0$ at every point sufficiently close to and to the right of $c$, then $c$ is a point of local minima.

If at $x=a$ the shape of the curve changes from increasing to decreasing or from decreasing to increasing. Then $\mathrm{x}=\mathrm{a}$ is known as the point of inflection and $f^{\prime \prime}(x)=0$ at $x=a$.

Important Formulae for Application of Derivatives

| Concept / Application | Derivative Condition | Interpretation / Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing Function | $f'(x) > 0$ | Function is strictly increasing in the interval |

| $f'(x) \ge 0$ | Function is increasing (non-decreasing) | |

| Decreasing Function | $f'(x) < 0$ | Function is strictly decreasing in the interval |

| $f'(x) \le 0$ | Function is decreasing (non-increasing) | |

| Maxima (Local Maximum) | $f'(x) = 0$ and $f''(x) < 0$ | Function attains a local maximum at $x$ |

| Minima (Local Minimum) | $f'(x) = 0$ and $f''(x) > 0$ | Function attains a local minimum at $x$ |

| Point of Inflexion | $f''(x) = 0$ and change in concavity | Curve changes concavity at $x$ |

| Slope of Tangent | $f'(x)$ | Derivative gives the slope of the tangent at any point |

| Rate of Change | $f'(x)$ | Instantaneous rate of change of quantity |

| Velocity (in motion problems) | $v = \frac{ds}{dt} = s'(t)$ | Derivative of displacement gives velocity |

| Acceleration (in motion problems) | $a = \frac{dv}{dt} = v'(t) = s''(t)$ | Derivative of velocity gives acceleration |

Application Of Derivatives in Mathematics: Solved Previous Year Questions

Question 1:

If $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )= \frac{x}{1+x}\; and\; g\left ( x \right )= ln\left ( 1+x \right ),\; then\; for\; x\in \left ( 0,\infty \right )}$

Solution:

$

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Let } \mathrm{h}(\mathrm{x})=\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})-\mathrm{g}(\mathrm{x}) \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{h}(\mathrm{x})=\frac{\mathrm{x}}{1+\mathrm{x}}-\ln (1+\mathrm{x}) \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{h}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=\frac{(1+\mathrm{x})-\mathrm{x}}{(1+\mathrm{x})^2}-\frac{1}{1+\mathrm{x}} \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{~h}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=\frac{1}{(1+\mathrm{x})^2}-\frac{1}{1+\mathrm{x}} \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{~h}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=\frac{-\mathrm{x}}{(1+\mathrm{x})^2}

\end{aligned}

$

For $\mathrm{x} \in(0, \infty)$

$

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{h}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{~h}(\mathrm{x}) \text { is a decreasing function } \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{h}(\mathrm{x})<\mathrm{h}(0) \text { for } \mathrm{x} \in(0, \infty) \\

& \Rightarrow \frac{\mathrm{x}}{1+\mathrm{x}}-\ln (1+\mathrm{x})<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \frac{\mathrm{x}}{1+\mathrm{x}}<\ln (1+\mathrm{x}) \\

& \Rightarrow \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})<\mathrm{g}(\mathrm{x})

\end{aligned}

$

Hence, the correct answer is $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )< g\left ( x \right )}$.

Question 2:

If $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )= x-\frac{x^{3}}{3}\; ,g\left ( x \right )= \tan^{-1}x\, ,\;then\; when\; x\in \left ( 0,1 \right ) ,}$

Solution:

$\begin{aligned} & \text { Let } h(x)=\left(x-\frac{x^3}{3}\right)-\tan ^{-1} x . \\ & \begin{aligned} \Rightarrow h^{\prime}(x) & =1-x^2-\frac{1}{1+x^2} \\ & =\left(1-\frac{1}{1+x^2}\right)-x^2 \\ & =\frac{x^2}{1+x^2}-x^2 \\ & =\frac{x^2-x^2-x^4}{1+x^2} \\ & =\frac{-x^4}{1+x^2}<0 \\ \therefore h^{\prime}(x) & <0\end{aligned} \\ & \Rightarrow h(x) \text { is decreasing function } \\ & \Rightarrow h(x)<h(0) \text { for } x \in(0,1) \\ & \Rightarrow x-\frac{x^3}{3}-\tan ^{-1} x<0 \\ & \Rightarrow x-\frac{x^3}{3}<\tan ^{-1} x .\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )< g\left ( x \right )}$.

Question 3:

$x=4$ is a point of maxima for function $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )}$ if

Solution:

Using the nth order derivative test, (4) is correct as for maxima, the first non-zero higher order derivative should have even order, and the value of the derivative should be negative.

Hence, the correct answer is "$\mathrm{f\,'\left ( 4 \right )= 0,f\,''\left ( 4 \right )= 0,f\,'''\left ( 4 \right )= 0,\: \: f^{IV}\left ( 4 \right )= -3}$".

Question 4:

If $\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )= x+\frac{1}{x}\, ,}$ then local minimum and local maximum values respectively are:

Solution:

$

\begin{aligned}

& \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})=\mathrm{x}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{x}_1} \\

& \mathrm{f}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=1-\frac{1}{\mathrm{x}^2}

\end{aligned}

$

So, $\mathrm{f}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=0$

$

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow 1-\frac{1}{x^2}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow 1=\frac{1}{x^2} \\

& \Rightarrow x^2=1 \\

& \Rightarrow x=1,-1

\end{aligned}

$

$

\begin{aligned}

& \mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(\mathrm{x})=\frac{2}{\mathrm{x}^3} \\

& \mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(1)=2>0 \Rightarrow \text { minima at } \mathrm{x}=1 \\

& \mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(-1)=-2<0 \Rightarrow \text { maxima at } \mathrm{x}=-1

\end{aligned}

$

Local minimum value $=\mathrm{f}(1)=1+1=2$

Local maximum value $=\mathrm{f}(-1)=-1-1=-2$

Note: Observe that the local minimum value at a point may be larger than the local maximum value.

Hence, the correct answer is $\mathrm{2,-2}$.

Question 5:

$\mathrm{f\left ( x \right )= x^{3}-3x+4}$ has local minimum at:

Solution:

$

f(x)=x^3-3 x+4

$

It is always differentiable.

So, only critical points are where $\mathrm{f}^{\prime}(\mathrm{x})=0$

$

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow 3 x^2-3=0 \\

& \Rightarrow 3\left(x^2-1\right)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow x=1,-1

\end{aligned}

$

For local minima, $\mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(\mathrm{x})>0$

$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(\mathrm{x}) & =\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{dx}}\left(3\left(\mathrm{x}^2-1\right)\right) \\

& =6 \mathrm{x}

\end{aligned}

$

For $\mathrm{x}=1, \mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(1)=6>0$

$\therefore$ Local minima at $\mathrm{x}=1$

For $\mathrm{x}=-1, \mathrm{f}^{\prime \prime}(-1)=-6<0$

$\therefore$ Local maxima at $\mathrm{x}=-1$

Hence, the correct answer is $\mathrm{x= 1}$.

Applications of Derivatives in Different Exams

The chapter on Applications of Derivatives is an important part of Class 12 Mathematics and focuses on the practical use of differentiation. It is frequently tested in board exams and competitive examinations. The table below highlights the exam-wise focus areas, commonly asked topics, and effective preparation strategies.

| Exam Name | Focus Area | Common Topics Asked | Preparation Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBSE Board | Conceptual clarity & application | Rate of change, increasing–decreasing functions, maxima and minima | Study the NCERT theory carefully and practise all textbook examples |

| JEE Main | Problem-solving & accuracy | Tangents and normals, monotonicity, maxima–minima | Practise MCQs and numerical-based questions regularly |

| JEE Advanced | Analytical thinking | Complex optimisation problems, advanced rate of change | Solve previous years’ advanced-level questions |

| NEET | Basics & speed | Simple applications of derivatives, monotonicity | Focus on quick formula application |

| State Board Exams (ICSE, UP Board, RBSE, etc) | Theory-oriented | Definitions, standard problems, basic applications | Revise textbook concepts and practice solved examples |

| Mathematics Olympiads | Concept application | Challenging optimisation and graph-based problems | Strengthen fundamentals and practise higher-level questions |

List of topics related to the Application of Derivatives according to NCERT/JEE Mains

This section covers all essential topics of the application of derivatives class 12 as per the NCERT and JEE Main syllabus, helping students focus on important concepts.

Important Books and Resources for the Application of Derivatives

Discover the best books and reference materials for mastering the application of derivatives, including NCERT resources, books, solutions, exemplar problems, etc.

| Book Title | Author / Publisher | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NCERT Class 12 Mathematics | NCERT | Official textbook covering all fundamental concepts and exercises on the application of derivatives. |

| Mathematics for Class 12 | R.D. Sharma | Detailed explanations, solved examples, and practice problems specifically on derivatives and their applications. |

| Objective Mathematics | R.S. Aggarwal | Includes MCQs and descriptive problems on topics including the application of derivatives. |

| Arihant All-In-One Mathematics | Arihant | Comprehensive coverage with theory, solved, and unsolved questions for JEE and boards. |

| Calculus Made Easy | M.L. Khanna | Simplified explanations and practical examples of derivatives and their real-world applications. |

NCERT Resources for Application of Derivatives

Explore official NCERT textbooks and solved examples that provide a clear and structured understanding of the application of derivatives class 12 formulas and solutions.

NCERT Subjectwise Resources

Access subject-specific NCERT resources, making it easier to practice and revise effectively.

| Subject | NCERT Notes Link | NCERT Solutions Link | NCERT Exemplar Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | NCERT Notes Class 12 Maths | NCERT Solutions for Class 12 Mathematics | NCERT Exemplar Class 12 Maths |

| Physics | NCERT Notes Class 12 Physics | NCERT Solutions for Class 12 Physics | NCERT Exemplar Class 12 Physics |

| Chemistry | NCERT Notes Class 12 Chemistry | NCERT Solutions for Class 12 Chemistry | NCERT Exemplar Class 12 Chemistry |

Practice Questions based on Applications of Derivatives

This section includes a collection of solved and unsolved problems designed to strengthen problem-solving skills in the application of derivatives class 12, covering real-life applications and competitive exam patterns.

Conclusion

The chapter Application of Derivatives plays a vital role in connecting theoretical calculus with real-life situations. It helps students analyse the behaviour of functions, solve optimisation problems, and understand practical concepts like speed, growth, and profit. Mastering this chapter builds a strong foundation for higher mathematics and physics and is especially important for Class 12 board exams and competitive exams like JEE and NEET. With regular practice of formulas and problems, students can score well and develop a clear understanding of how derivatives are applied in mathematics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

By using first and second derivative tests, we can determine the points where a function attains a maximum or minimum value, which is useful in optimizing profits, area, volume, or cost.

A function is increasing if its derivative $f'(x) > 0$, and decreasing if $f'(x) < 0$. Derivatives help identify where a function rises or falls in a given interval.

A point of inflection occurs where the second derivative $f''(x) = 0$ and the concavity of the function changes. It shows where a curve changes from concave up to concave down or vice versa.

Key formulas include $f'(x) > 0$ for increasing, $f'(x) < 0$ for decreasing, $f'(x) = 0$ and $f''(x) > 0$ for minima, $f'(x) = 0$ and $f''(x) < 0$ for maxima, and $f''(x) = 0$ for points of inflection.

Because derivatives represent slope, we may use them to calculate the maxima and minima of a variety of functions. They can also be used to express at what rate a function is changing.