Geometrical Interpretation of Product of Vectors

Imagine trying to understand not just how big two vectors are, but how they are positioned with respect to each other in space. That’s where the geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors becomes really powerful. Instead of treating dot product and cross product as just formulas, we visualize them as measures of angles, projections, areas, and directions. In mathematics, these interpretations give a clear geometric meaning to vector operations and make problem-solving much more intuitive. In this article, we will explore the geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors, including the dot product and cross product, with clear explanations and visual understanding.

This Story also Contains

- Geometrical Interpretation of Scalar Product (Dot Product) in Vector Algebra

- Geometrical Interpretation of Scalar Product Using Projections

- What is Vector Product (Cross Product)?

- Geometrical Interpretation of Vector Product (Cross Product) in Vector Algebra

- Area of Parallelogram Using Vector Product

- Area of Triangle Using Vector Product

- Important Notes on Area Using Vector Algebra

- Solved Examples Based on Geometrical Interpretation of Product of Vectors

- List of Topics Related to Geometrical interpretation of the Product of vectors

- NCERT Resources

- Practice Questions based on Geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors

Geometrical Interpretation of Scalar Product (Dot Product) in Vector Algebra

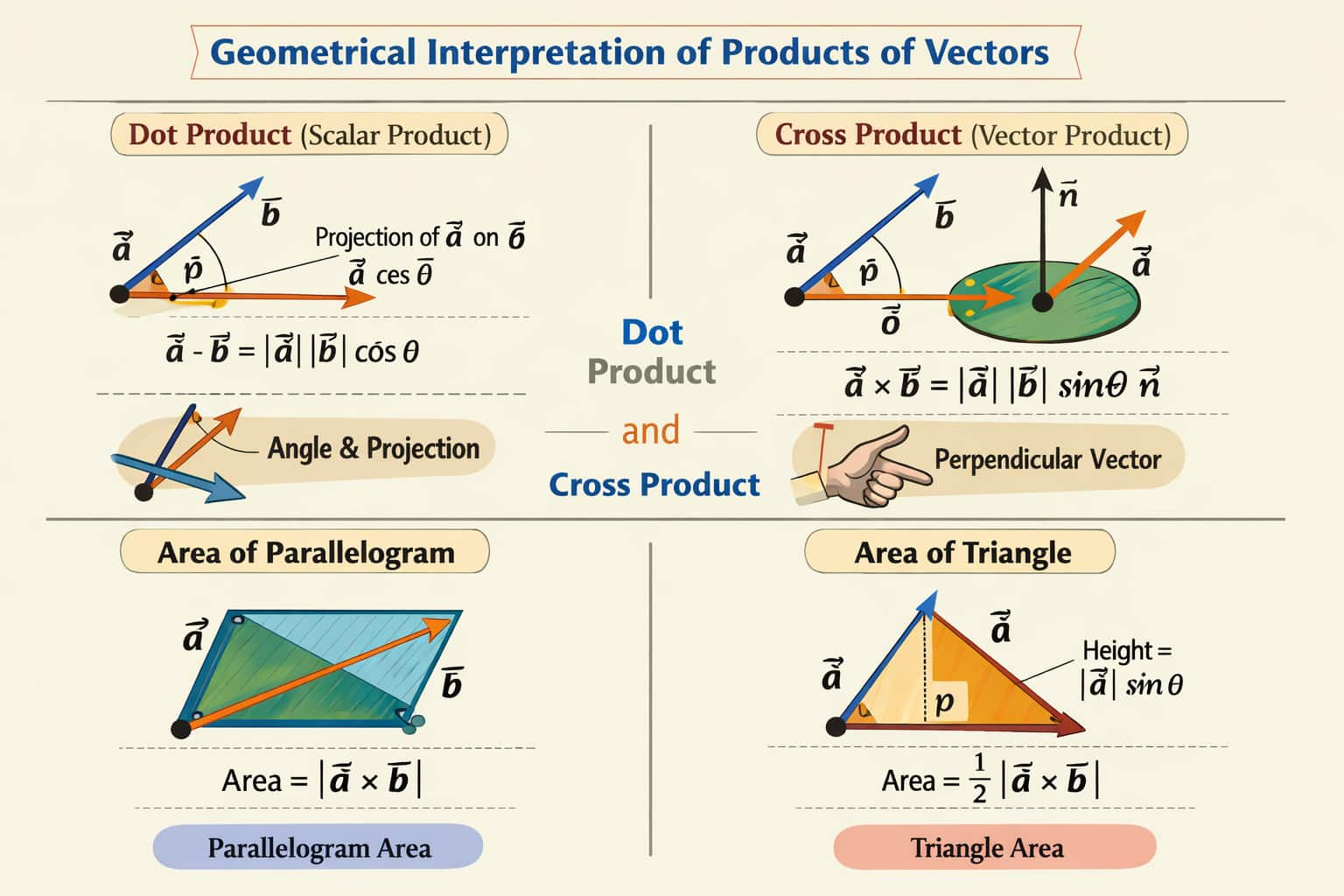

The geometrical interpretation of the scalar product, also known as the dot product, explains how two vectors are related in terms of their direction and alignment in space. Instead of viewing the dot product as just a formula, we understand it geometrically as the product of the magnitude of one vector and the projection of the other vector on it. This interpretation is extremely important in Vector Algebra, especially for understanding angles, projections, and vector components.

Definition of Scalar Product in Vector Algebra

If $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ are two non-zero vectors, then their scalar product (or dot product) is defined as

$\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\cos\theta,\quad (0\le\theta\le\pi)$

where $\theta$ is the angle between the vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$.

This formula shows that the dot product depends on both:

The magnitudes of the vectors

The angle between them

Geometrical Meaning of Dot Product

Let $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ be represented by the directed line segments $OA$ and $OB$ respectively.

Draw

$BL \perp OA$ and $AM \perp OB$.

From triangles $OBL$ and $OAM$, we get

$OL = OB\cos\theta$

$OM = OA\cos\theta$

Here:

$OL$ is called the projection of vector $\vec{b}$ on vector $\vec{a}$

$OM$ is called the projection of vector $\vec{a}$ on vector $\vec{b}$

So, the scalar product can be written as

$\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=|\vec{a}|( \text{projection of } \vec{b} \text{ on } \vec{a})$

or

$\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=|\vec{b}|( \text{projection of } \vec{a} \text{ on } \vec{b})$

Geometrical Interpretation of Scalar Product Using Projections

The geometrical meaning of the scalar (dot) product can be clearly understood using the concept of projection of one vector on another. It shows how much one vector acts in the direction of the other.

$\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\cos\theta$

$=|\vec{a}|(OB\cos\theta)$

$=|\vec{a}|(OL)$

$=(\text{magnitude of }\vec{a})(\text{projection of }\vec{b}\text{ on }\vec{a})$

Again,

$\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\cos\theta$

$=|\vec{b}|(|\vec{a}|\cos\theta)$

$=|\vec{b}|(OA\cos\theta)$

$=|\vec{b}|(OM)$

$=(\text{magnitude of }\vec{b})(\text{projection of }\vec{a}\text{ on }\vec{b})$

Thus, geometrically, the scalar product of two vectors is equal to the product of the magnitude of either vector and the projection of the other vector on it. This makes the dot product a powerful tool for understanding alignment and direction in Vector Algebra.

Formula for Projection of One Vector on Another

Projection of $\vec{a}$ on $\vec{b}$ is:

$\text{Projection of }\vec{a}\text{ on }\vec{b}=\frac{\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}}{|\vec{b}|}

=\vec{a}\cdot\frac{\vec{b}}{|\vec{b}|}

=\vec{a}\cdot\hat{b}$

Projection of $\vec{b}$ on $\vec{a}$ is:

$\text{Projection of }\vec{b}\text{ on }\vec{a}=\frac{\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}}{|\vec{a}|}

=\vec{b}\cdot\frac{\vec{a}}{|\vec{a}|}

=\vec{b}\cdot\hat{a}$

These formulas are widely used in Vector Algebra, physics, and engineering to find vector components along given directions.

Importance of Geometrical Interpretation of Dot Product

The geometrical interpretation of the dot product helps in:

Finding the angle between two vectors

Calculating vector projections

Checking whether two vectors are perpendicular

Solving problems in physics, engineering, and 3D geometry

If $\vec{a}\cdot\vec{b}=0$, then $\theta=90^\circ$, which means the vectors are perpendicular.

What is Vector Product (Cross Product)?

The vector product, also known as the cross product, of two non-zero vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ is denoted by $\vec{a}\times\vec{b}$ and is defined as:

$\vec{a}\times\vec{b}=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta,\hat{n}$

where:

$\theta$ is the angle between $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$, with $0\le\theta\le\pi$

$\hat{n}$ is a unit vector perpendicular to both $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$

The direction of $\hat{n}$ is given by the right-hand rule, such that $\vec{a}$, $\vec{b}$, and $\hat{n}$ form a right-handed system

Geometrical Interpretation of Vector Product (Cross Product) in Vector Algebra

The geometrical interpretation of the vector product, also called the cross product, explains how two vectors interact in space to produce a new vector that represents both magnitude and direction. Unlike the dot product, which gives a scalar, the vector product always gives a vector perpendicular to the plane containing the given vectors. This makes the cross product extremely important in Vector Algebra, 3D geometry, and physics.

The vector product of two non-zero vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ is denoted by $\vec{a}\times\vec{b}$ and is defined as:

$\vec{a}\times\vec{b}=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta,\hat{n}$

where:

$\theta$ is the angle between $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$, with $0\le\theta\le\pi$

$\hat{n}$ is a unit vector perpendicular to both $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$

The direction of $\hat{n}$ is given by the right-hand rule, such that $\vec{a}$, $\vec{b}$, and $\hat{n}$ form a right-handed system

This definition shows that the cross product depends on:

The magnitudes of the vectors

The sine of the angle between them

The orientation of the plane formed by the vectors

Geometrical Meaning of the Cross Product

Geometrically, the magnitude of $\vec{a}\times\vec{b}$ represents the area of the parallelogram formed by vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ as adjacent sides.

The direction of $\vec{a}\times\vec{b}$ is perpendicular to the plane of the parallelogram.

Thus, the vector product connects:

Geometry (area and perpendicular direction)

Algebra (vector operations and magnitudes)

Area of Parallelogram Using Vector Product

The area of a parallelogram is the region enclosed by two intersecting sides. If $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ are two non-zero, non-parallel vectors representing two adjacent sides of a parallelogram, then the area is given by:

$\text{Area of parallelogram}=|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|$

Let $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ be represented by the directed line segments $AD$ and $AB$ respectively, and let $\theta$ be the angle between them.

Then,

$|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta$

which is exactly the formula for the area of a parallelogram in geometry:

$\text{Area} = \text{base} \times \text{height}$

Here:

$|\vec{a}|$ or $|\vec{b}|$ acts as the base

$|\vec{b}|\sin\theta$ or $|\vec{a}|\sin\theta$ acts as the height

From geometry, consider $\triangle ADE$:

$\sin\theta=\frac{DE}{AD}$

$\Rightarrow DE=AD\sin\theta=|\vec{a}|\sin\theta$

Now, the area of parallelogram $ABCD$ is:

$\text{Area of parallelogram }ABCD=AB\times DE$

$=|\vec{b}|,(|\vec{a}|\sin\theta)$

$=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta$

But we know,

$|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta$

Hence,

$\text{Area of parallelogram }ABCD=|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|$

This proves that the magnitude of the cross product of two vectors gives the area of the parallelogram formed by them. This is one of the most important geometrical interpretations of the vector product in Vector Algebra.

Area of Triangle Using Vector Product

The area of a triangle is the region enclosed by three sides in a plane.

If $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ are two non-zero, non-parallel vectors representing two adjacent sides of a triangle, then the triangle is exactly half of the parallelogram formed by these vectors.

So, the area of the triangle is:

$\text{Area of triangle}=\frac{1}{2},|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|$

We know from basic geometry that the area of a triangle is

$\text{Area of triangle}=\frac{1}{2}\times(\text{Base})\times(\text{Height})$

From the figure,

$\text{Area of } \triangle ABC=\frac{1}{2},AB\cdot CD$

But

$AB=|\vec{b}|$ (given)

and

$CD=|\vec{a}|\sin\theta$

Therefore,

$\text{Area of } \triangle ABC=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{b}|,(|\vec{a}|\sin\theta)$

$=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta$

But we know,

$|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|=|\vec{a}||\vec{b}|\sin\theta$

Hence,

$\text{Area of } \triangle ABC=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{a}\times\vec{b}|$

This shows that the area of a triangle formed by two vectors is half the magnitude of their cross product, which is a key result in the geometrical interpretation of vector product.

Important Notes on Area Using Vector Algebra

1. Area of a parallelogram in terms of its diagonals

If $\vec{d}_1$ and $\vec{d}_2$ are the diagonals of a parallelogram, then

$\text{Area of parallelogram}=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{d}_1\times\vec{d}_2|$

2. Area of a plane quadrilateral using diagonals

If $ABCD$ is a plane quadrilateral and $AC$ and $BD$ are its diagonals, then

$\text{Area of quadrilateral }ABCD=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{AC}\times\vec{BD}|$

3. Area of a triangle using position vectors

If $\vec{a}$, $\vec{b}$, and $\vec{c}$ are the position vectors of the vertices $A$, $B$, and $C$ of a triangle, then its area is

$\text{Area of } \triangle ABC

=\frac{1}{2}\left|(\vec{a}\times\vec{b})+(\vec{b}\times\vec{c})+(\vec{c}\times\vec{a})\right|$

Solved Examples Based on Geometrical Interpretation of Product of Vectors

Example 1: Let for a triangle ABC,

$\begin{aligned} & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}=-2 \hat{\mathrm{i}}+\hat{\mathrm{j}}+3 \hat{\mathrm{k}} \\ & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}}=\alpha \hat{\mathrm{i}}+\beta \hat{\mathrm{j}}+\gamma \hat{\mathrm{k}} \\ & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CA}}=4 \hat{\mathrm{i}}+3 \hat{\mathrm{j}}+\delta \hat{\mathrm{k}}\end{aligned}$

If $\delta>0$ and the area of the triangle ABC is $5 \sqrt{6}$, then $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CA}}$ is equal to [JEE MAINS 2023]

Solution

$\begin{aligned} & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CA}}+\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}} \\ & \langle 4,3, \delta\rangle \cdot+\langle-2,1,3\rangle=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}} \\ & \Rightarrow \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}}=\langle 2,4,3+\delta\rangle\end{aligned}$

$\begin{aligned} & \Rightarrow|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}|^2=600 \\ & \Rightarrow 5 \delta^2+30 \delta-275=0 \\ & \Rightarrow \mathrm{S}^2+6 \delta-55=0 \\ & \Rightarrow(\delta+11)(\delta-5)=0 \\ & \delta=5 \\ & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}}=<2,3,8> \\ & \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CB}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CA}} \cdot=<2,4,8>\cdot<4,3,5> \\ & =8+12+40=60\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is 60

Example 2: Let $\vec{a}=4 \hat{i}+3 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k}$ and $\vec{\beta}=\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-4 \hat{k}$, Let $\vec{\beta}_1$ be parallel to $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{\beta}_2$ be perpendicular to $\vec{a}$.If $\vec{\beta}=\vec{\beta}_1+\vec{\beta}_2$, then the value of $5 \vec{\beta}_2 \cdot(\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k})$ is [JEE MAINS 2023]

Solution

$

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{\beta}_1=\frac{(\vec{\alpha} \cdot \vec{\beta})}{|\vec{\alpha}|} \hat{\alpha} \\

& =\left(\frac{4+6-20}{\sqrt{16+9+25}}\right) \frac{(4,3,5)}{\sqrt{50}} \\

& =\frac{-10}{50}(4,3,5) \\

& \vec{\beta}_1=\frac{(-4,-3,-5)}{5} \\

& \vec{\beta}_1+\vec{\beta}_2-=(1,2,-4) \\

& \beta_2=\left(1+\frac{4}{5}, 2+\frac{3}{5},-4+1\right) \\

& \beta_2=\left(\frac{9}{5}, \frac{13}{5},-3\right) \\

& \therefore 5 \beta_2=(9,13,-15) \\

& \therefore 5 \beta_2 \cdot(1,1,1)=9+13-15 \\

& =7

\end{aligned}

$

Hence, the answer is 7

Example 3: If $\mathrm{a}^{\prime}=\hat{\imath}+2 k, b=\hat{\imath}+\hat{\jmath}+k, \vec{c}=7 \hat{\imath}-3 \hat{\jmath}+4 k, \mathrm{r}^{\prime} \times \mathrm{b}+\mathrm{b} \times \mathrm{c}^{\prime}=0$ and $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{r}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{a}}=0$. Then $\vec{r} \cdot \vec{c}$ is equal to

Solution

$

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{r} \times \vec{b}+\vec{b} \times \vec{c}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \vec{r} \times \vec{b}-\vec{c} \times \vec{b}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow(\vec{r}-\vec{c}) \times \vec{b}=0 \\

& \vec{r}-\vec{c} \| \vec{b} \\

& \vec{r}-\vec{c}=\lambda \vec{b} \\

& \vec{r}=\lambda \vec{b}+\vec{c} \\

& =\lambda(i+j+k)+(7 i-3 j+4 k) \\

& =\mathrm{i}(\lambda+7)+j(\lambda-3)+\mathrm{k}(\lambda+4) \\

& \vec{r} \cdot \vec{a}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow(7+\lambda)+2(\lambda+4)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow 3 \lambda=-15 \Rightarrow \lambda=-5 \\

& \therefore \vec{r}=2 \mathrm{i}-8 \mathrm{j}-\mathrm{k} \\

& \overrightarrow{\mathrm{r}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{c}}=(2 \mathrm{i}-8 \mathrm{j}-\mathrm{k}) \cdot(7 \mathrm{i}-3 \mathrm{j}+4 \mathrm{k}) \\

& =14+24-4=34

\end{aligned}

$

Hence, the answer is 34

Example 4: Let $\vec{a}=\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k}, \vec{b}=\hat{i}-2 \hat{j}$ and $\vec{c}=\hat{i}-\hat{j}-\hat{k}$ be three given vectors. If $\vec{r}$ is a vector such that $\vec{r}$ is a vector such that $\vec{r} \times \vec{a}=\vec{c} \times \vec{a}$ and $\vec{r} \cdot \vec{b}=0$, then $\vec{r} \cdot \vec{a}$ is equal to

Solution

$

\begin{aligned}

& (\vec{r}-\vec{c}) \times \vec{a}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \vec{r}=\vec{c}+\lambda \vec{a}

\end{aligned}

$

Now, $0=\vec{b} \cdot \vec{c}+\lambda \vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}$

$

\Rightarrow \lambda=\frac{-\vec{b} \cdot \vec{c}}{\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}}=-\frac{2}{-1}=2

$

So, $\vec{r} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{a}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{a}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{c}}+2 \mathrm{a}^2=12$

Hence, the answer is 12

Example 5: The area (in sq. units) of the parallelogram whose diagonals are along the vectors $8 \hat{i}-6 \hat{j}$ and $3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-12 \hat{k}$, [JEE MAINS 2017]

Solution: Area of parallelogram $=\frac{1}{2}|\vec{a} \times \vec{b}|$

where $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ are diagonals

$

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{1}{2}\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\

8 & -6 & 0 \\

3 & 4 & -12

\end{array}\right| \\

& =\left|\frac{1}{2}(72 \hat{i}+96 \hat{j}+50 \hat{k})\right| \\

& =|36 \hat{i}+48 \hat{j}+25 \hat{k}| \\

& \text { magnitude }=\sqrt{36^2+48^2+25^2} \\

& =65

\end{aligned}

$

Hence, the answer is 65.

List of Topics Related to Geometrical interpretation of the Product of vectors

This section gives a clear overview of all the key Vector Algebra topics that support the geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors. It helps you understand the basic concepts needed to visualise and apply vector products more effectively.

Addition of Vectors and Subtraction of Vectors

Multiplication Of Vectors by a Scalar Quantity

Components Of A Vector Along And Perpendicular To Another Vector

NCERT Resources

This section brings together all essential NCERT resources related to Vector Algebra in one place. It helps you study directly from syllabus-based material and strengthen your concepts with clear notes and well-explained solutions.

NCERT Maths Class 12th Notes for Chapter 10 - Vector Algebra

NCERT Maths Class 12th Solutions for Chapter 10 - Vector Algebra

NCERT Maths Class 12th Exemplar Solutions for Chapter 10 - Vector Algebra

Practice Questions based on Geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors

This section includes specially designed practice questions to help you apply the geometrical interpretation of the product of vectors with confidence. It focuses on improving conceptual clarity, accuracy, and problem-solving skills through exam-oriented MCQs and practice problems.

Geometrical Interpretation Of Product Of Vectors- Practice Question MCQ

We have provided below the practice questions based on the topics related to Geometrical interpretation of Product of vectors:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

It means understanding dot product and cross product using geometry, such as angles, projections, areas, and perpendicular directions, instead of seeing them as only algebraic formulas.

The dot product represents the product of the magnitude of one vector and the projection of the other vector on it, and it helps in finding angles and checking perpendicularity.

The area of a parallelogram formed by vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ is $|\vec{a} \times \vec{b}|$.

The area of a triangle formed by vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ is

$\frac{1}{2}|\vec{a} \times \vec{b}|$.

If $\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b} = 0$, then the vectors are perpendicular to each other.