Definite Integral as Limit of a Sum

Imagine you’re trying to figure out how much paint you need to cover a weirdly–shaped wall — not a neat rectangle, but something curved and uneven. Measuring each tiny piece separately would take forever, right? Instead, you’d break the wall into many small strips, estimate each one, and then add them all up. As you make the strips thinner and more numerous, your total gets closer and closer to the exact amount of paint needed. That’s exactly the heart of definite integrals as the limit of a sum: we approximate an area by slicing it into infinitely many tiny rectangles and then take the limit of their total. This idea is the foundation of integral calculus — the bridge between discrete summation and continuous measurement — and it shows how integrals naturally arise from simple, intuitive approximations. In this article, we’ll explore how definite integrals are defined using Riemann sums, why the limit process works, the standard formulas, worked examples, and how this concept appears in real-world problems and competitive exam questions in mathematics.

This Story also Contains

- Definite integral as the limit of a sum

- Step-by-Step Derivation of the Limit Definition

- Solved Examples Based on Integration as Limit of Sum

- List of Topics Related to the Definite Integral as limit of a sum

- NCERT Resources

- Practice Questions based on Definite Integral as limit of a sum

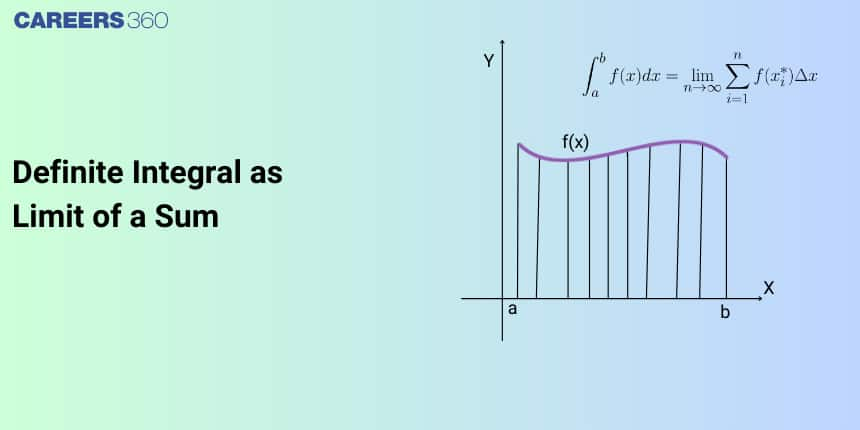

Definite integral as the limit of a sum

Definite integration calculates the area under a curve between two specific points on the x-axis.

Let f be a function of x defined on the closed interval [a, b] and F be another function such that $\frac{d}{d x}(F(x))=f(x)$ for all x in the domain of f, then

$\int_a^b f(x) d x=[F(x)+c]_a^b=F(b)-F(a)$is called the definite integral of the function f(x) over the interval [a, b], where a is called the lower limit of the integral and b is called the upper limit of the integral.

Let f(x) be a continuous real-valued function defined on the closed interval [a, b] which is divided into n parts as shown in the figure.

Each subinterval denoted as $\left[x_0, x_1\right],\left[x_1, x_2\right], \ldots\left[x_{i-1}, x_i\right], \ldots,\left[x_{n-1}, x_n\right]$ having equal width $\frac{b-a}{n}$ where, $x_0=a$ and $x_n=b$.

$

\Rightarrow \quad x_i-x_{i-1}=\frac{b-a}{n} \quad \text { for } i=1,2,3, \ldots, n

$

We denote the width of each subinterval with the notation $\Delta x$, so $\quad \Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}$ and $x_i=x_0+i \Delta x$

On each subinterval,$\left.x_{i-1}, x_i\right]$ (for $\left.i=1,2,3, \ldots, n\right)$ a rectangle is constructed with width Δx and height equal to$f\left(x_{i-1}\right)$ which is the function value at the left endpoint of the subinterval. Then the area of this rectangle is s $f\left(x_{i-1}\right) \Delta x$. Adding the areas of all these rectangles, we get an approximate value for A

$\begin{aligned} A \approx L_n & =f\left(x_0\right) \Delta x+f\left(x_1\right) \Delta x+\cdots+f\left(x_{n-1}\right) \Delta x \\ & =\sum_{i=1}^n f\left(x_{i-1}\right) \Delta x\end{aligned}$

$\mathrm{L}_n$ to denote that this is a left-endpoint approximation of A using n subintervals.

The second method for approximating the area under a curve is the right-endpoint approximation. It is almost the same as the left-endpoint approximation, but now the heights of the rectangles are determined by the function values at the right of each subinterval.

This time the height of the rectangle is determined by the function value f(xi) at the right endpoint of the subinterval. Then, the area of each rectangle is f(xi)Δx and the approximation for A is given by

$\begin{aligned} A \approx R_n & =f\left(x_1\right) \Delta x+f\left(x_2\right) \Delta x+\cdots+f\left(x_n\right) \Delta x \\ & =\sum_{i=1}^n f\left(x_i\right) \Delta x\end{aligned}$

As $\mathrm{n} \rightarrow \infty$ strips become narrower and narrower, it is assumed that the limiting values of $L_n$ and $R_n$ are the same in both cases and the common limiting value is the required area under the curve.

Symbolically, we write

$\begin{aligned} & \lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \mathrm{L}_n=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \mathrm{R}_{\mathrm{n}}=\text { area of the region }=\int_a^b f(x) d x \\ & \int_a^b f(x) d x=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(x_i\right) \Delta x=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n\left(\frac{b-a}{n}\right) f\left(a+\left(\frac{b-a}{n}\right) i\right) \\ & \text { where, } \quad \Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n} \text { and } x_i=x_0+\Delta x . i\end{aligned}$

NOTE:

If $\mathrm{a}=0, \mathrm{~b}=1$, then

$\int_0^1 f(x) d x=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \frac{1}{n} f\left(\frac{i}{n}\right)$

From the definition of definite integral, we have

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=\varphi(n)}^{\psi(n)} f\left(\frac{i}{n}\right)=\int_a^b f(x) d x$, where

(i) $\quad \Sigma$ is replaced by $\int$ sign

(ii) $\frac{i}{n}$ is replaced by $x$

(iii) $\frac{1}{n}$ is replaced by $d x$

(iv) To obtain the limits of integration, we use $\mathrm{a}=\lim _{\mathrm{n} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\phi(\mathrm{n})}{\mathrm{n}}$ and $\mathrm{b}=\lim _{\mathrm{n} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\psi(\mathrm{n})}{\mathrm{n}}$

For example:

$\begin{aligned} & \lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{r=1}^{p . n} \frac{1}{n} f\left(\frac{r}{n}\right)=\int_\alpha^\beta f(x) d x \\ & \text { where, } \alpha=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{r}{n}=0(\text { as } r=1) \\ & \text { and } \quad \beta=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{r}{n}=p(\text { as } r=p n)\end{aligned}$

Step-by-Step Derivation of the Limit Definition

Understand the fundamental concept of definite integrals through a detailed step-by-step derivation of the limit definition. This section breaks down the process of expressing integrals as limits of sums, building a strong foundation for integral calculus.

Partition of an Interval

To begin formalizing the idea of area under a curve, we break the interval $[a,b]$ into $n$ smaller pieces. This collection of $n$ segments is called a partition. Each point in the partition helps us approximate the total area using simple geometric shapes.

Width of Each Subinterval $ \Delta x $

Once the interval is divided, each subinterval has width

$ \Delta x = \frac{b-a}{n} $.

This fixed width ensures that as $n$ increases, the subintervals become finer, giving us a more accurate approximation of the area under $f(x)$.

Sum of Areas of Rectangles

For each subinterval, we pick a sample point $x_i$ and build a rectangle whose height is $f(x_i)$ and whose width is $\Delta x$. The total approximate area is then

$ \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(x_i),\Delta x $.

This sum is called a Riemann sum, and it becomes more accurate as the rectangles get thinner.

Taking the Limit $ n \to \infty $

The key idea is that as we increase $n$, the rectangles fit the curve more closely. The moment $n$ approaches infinity, the approximation becomes exact. This limiting process is what transforms the Riemann sum into a definite integral.

Final Definition

Using all the steps above, the definite integral of $f(x)$ over $[a,b]$ is formally defined as:

$ \int_a^b f(x),dx = \lim_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(x_i)\Delta x $

This definition anchors the entire concept of integration — it is the bridge between discrete summation and continuous accumulation.

Solved Examples Based on Integration as Limit of Sum

Example 1: $\int_0^3\{x\} d x$

1) 2

2) 3/2

3) 4

4) 5

Solution

Definite Integrals as the limit of a sum -

$\int_0^l f(x) d x=\lim _{x \rightarrow \infty} \sum \frac{1}{x} f\left(\frac{r}{x}\right)$

Or

$\int_a^b f(x) d x=\lim _{x \rightarrow \infty} h \sum_{r=0}^x f(a+r h)$

- wherein

Where $f(x)$ is a continuous function in $[0, l]$

Where $h=\frac{b-a}{x}$ And $f(x)$ is continuous in $[a, b]$

$\int_0^3\{x\}=\int_0^1\{x\} d x+\int_1^2\{x\} d x+\int_2^3\{x\} d x$

$=3 / 2$

Example 2: $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left[\frac{1}{n}+\frac{n}{(n+1)^2}+\frac{n}{(n+2)^2}+\ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots+\frac{n}{(2 n-1)^2}\right]$ is equal to:

1) $\frac{1}{2}$

2) 1

3) $\frac{1}{3}$

4) $\frac{1}{4}$

Solution

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left[\frac{1}{n}+\frac{n}{(n+1)^2}+\frac{n}{(n+2)^2}+\ldots+\frac{n}{(2 n-1)^2}\right]$

$\begin{aligned} & =\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{r=0}^{n-1} \frac{n}{(n+r)^2}=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{r=0}^{n-1} \frac{n}{n^2+2 n r+r^2} \\ & =\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{r=0}^{n-1} \frac{1}{(r / n)^2+2(r / n)+1}\end{aligned}$

$=\int_0^1 \frac{\mathrm{dx}}{(\mathrm{x}+1)^2}=\left[\frac{-1}{(\mathrm{x}+1)}\right]_0^1=\frac{1}{2}$

Hence, the answer is the option (1).

Example 3: $\left.\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\frac{(n+1)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}\right)+\frac{(n+2)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}+\ldots \ldots \ldots+\frac{(2 n)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}\right)$ is equal to:

1) $\frac{3}{4}(2)^{\frac{4}{3}}-\frac{3}{4}$

2) $\frac{4}{3}(2)^{\frac{4}{3}}$

3) $\frac{3}{4}(2)^{\frac{4}{3}}-\frac{4}{3}$

4) $\frac{4}{3}(2)^{\frac{3}{4}}$

Solution

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\frac{(n+1)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}+\frac{(n+2)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}+\ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots+\frac{(2 n)^{\frac{1}{3}}}{(n)^{\frac{4}{3}}}\right)$

$=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n}\left[\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}+\left(1+\frac{2}{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}+\ldots \ldots \ldots+\left(1+\frac{n}{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}\right]$

$\begin{aligned} & =\frac{1}{n} \sum_{r=1}^n\left(1+\frac{r}{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}} \\ & =\int_0^1(1+x)^{\frac{1}{3}} d x=\frac{3}{4}\left(2^{\frac{4}{3}}-1\right)\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is option (1).

Example 4: $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+1\right)(n+1)}+\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+4\right)(n+2)}+\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+9\right)(n+3)}+\ldots+\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+n^2\right)(n+n)}\right)$

1) $\frac{\pi}{8}+\frac{1}{4} \log _e 2$

2) $\frac{\pi}{4}+\frac{1}{8} \log _e 2$

3) $\frac{\pi}{4}-\frac{1}{8} \log _{\mathrm{e}} 2$

4) $\frac{\pi}{8}+\log _c \sqrt{2}$

Solution:

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+1\right)(n+1)}+\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+4\right)(n+2)}+\cdots+\frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+n^2\right)(n+n)}\right)$

$=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{r=1}^n \frac{n^2}{\left(n^2+r^2\right)(n+r)}$

$=\int_0^1 \frac{1}{\left(1+x^2\right)(1+x)} d x$

$\begin{aligned} & =\frac{1}{2} \int_0^1 \frac{1}{1+x} d x+\frac{1}{2} \int_b^1 \frac{d x}{1+x^2}-\frac{1}{4} \int_0^1 \frac{2 x}{\left(1+x^2\right)} d x \\ & =\frac{1}{2}[\ln (1+x)]_0^1+\frac{1}{2}\left[\tan ^{-1} x\right]_0^1-\frac{1}{4}\left[\ln \left(1+x^2\right)\right]_0^1 \\ & =\frac{1}{2} \ln 2+\frac{\pi}{8}-\frac{1}{4} \ln 2 \\ & =\frac{\pi}{8}+\frac{1}{4} \log e^2\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is the option (1).

Example 5: If $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(n+1)^{k-1}}{n^{k+1}}[(n k+1)+(n k+2)+\ldots+(n k+n)$$=33 \cdot \lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n^{k+1}} \cdot\left[1^k+2^k+3^k+\ldots+n^k\right]$,

then the integral value of $k$ is equal to _______.

1) 5

2) 9

3) 8

4) 6

Solution

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(n+1)^{k-1}}{n k+1}[n k \cdot n+1+2+\cdots+n]$

$=\lim _{\mathrm{n} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(\mathrm{n}+1)^{\mathrm{k}-1}}{\mathrm{n}^{\mathrm{k}+1}} \cdot\left[\mathrm{n}^2 \mathrm{k}+\frac{(\mathrm{n}(\mathrm{n}+1)}{2}\right]$

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(n+1)^{k-1} \cdot n^2\left(k+\frac{\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)}{2}\right)}{n k+1}$

$\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)\left(k+\frac{\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)}{2}\right)$

$\Rightarrow\left(k+\frac{1}{2}\right)$

RHS

$\Rightarrow \lim _{\mathrm{n} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{\mathrm{nk}+1}\left(1^{\mathrm{k}}+2^{\mathrm{k}}+\cdots+\mathrm{h}^{\mathrm{k}}\right)=\frac{1}{\mathrm{k}+1}$

LHS=RHS

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{k}+\frac{1}{2}=33 \cdot \frac{1}{\mathrm{k}+1}$

$\begin{aligned} & \Rightarrow(2 k+1)(k+1)=66 \\ & \Rightarrow(k-5)(2 k+13)=0 \\ & \Rightarrow k=5 \text { or } \frac{13}{9}\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is the (5).

List of Topics Related to the Definite Integral as limit of a sum

Explore essential topics connected to definite integrals defined as limits of sums, including applications of integrals, integrals of particular functions, indefinite integrals, integration by parts, and inequalities in definite integration, all crucial for a solid calculus foundation. These topics provide a comprehensive framework for mastering the concept and its applications in advanced mathematics.

Integral of Particular Functions

NCERT Resources

Access comprehensive NCERT resources for Class 12 Maths Chapter 7 – Integrals. Explore detailed notes, complete solutions, and exemplar problem sets to strengthen your understanding and excel in exams.

NCERT Class 12 Maths Notes for Chapter 7 - Integrals

NCERT Class 12 Maths Solutions for Chapter 7 - Integrals

NCERT Class 12 Maths Exemplar Solutions for Chapter 7 - Integrals

Practice Questions based on Definite Integral as limit of a sum

Test your understanding of definite integrals expressed as the limit of a sum with these carefully designed MCQs. Strengthen your JEE Main preparation through concept-based practice and application-focused questions.

Definite Integral As The Limit Of A Sum- Practice Question MCQ

We have provided below the practice questions related to different concepts of integration to improve your understanding:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

A definite integral is defined as the limit of a Riemann sum, where the interval $[a,b]$ is divided into smaller subintervals, summing the product of function values and subinterval widths as the partition size approaches zero.

Yes, a definite integral is negative if the function is below the x-axis over the interval, representing the signed area.

An indefinite integral gives a family of functions (antiderivatives) without limits, including a constant of integration, while a definite integral calculates the exact area between the curve and the x-axis over a specific interval.

Geometrically, a definite integral calculates the net area between the graph of the function and the x-axis, considering areas above the axis as positive and below as negative.

Evaluate a definite integral using the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: find the antiderivative $F(x)$ of $f(x)$, then compute $F(b)−F(a)$.