Newton-Leibnitz's Formula

Imagine you’re trying to assemble a big LEGO model, but instead of building it all at once, you break it into small, manageable chunks that fit together perfectly. That’s exactly how Newton’s–Leibniz formula works in mathematics - it connects differentiation and integration in a beautifully simple way, letting you compute definite integrals by just evaluating an antiderivative at two points. It takes a process that should feel long and tedious, and turns it into something quick, elegant, and surprisingly friendly once you get the hang of it. In this article, we’ll explore the Newton–Leibniz formula, why it works, how to use it, and where it becomes a game-changer in solving definite integrals.

This Story also Contains

- Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem

- Proof of Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem (Step-by-Step)

- Special Cases of Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem

- Applications of Newton–Leibniz’s Formula

- Practical Tips for Using Newton–Leibniz in Exams

- Solved Examples Based on Newton Leibnitz's Theorem

- List of Topics Related to Newton-Leibnitz's Formula

- NCERT Resources

- Practice Questions based on Newton-Leibnitz's Formula

Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem

Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem is basically the bridge that connects differentiation and integration. Think of it like this — imagine you're tracking how much water has filled a tank between two marks that themselves keep moving. If those marks move, the total water between them changes… and Newton–Leibniz tells us exactly how fast that change happens.

It gives a direct formula to differentiate a definite integral whose limits themselves are functions, not constants.

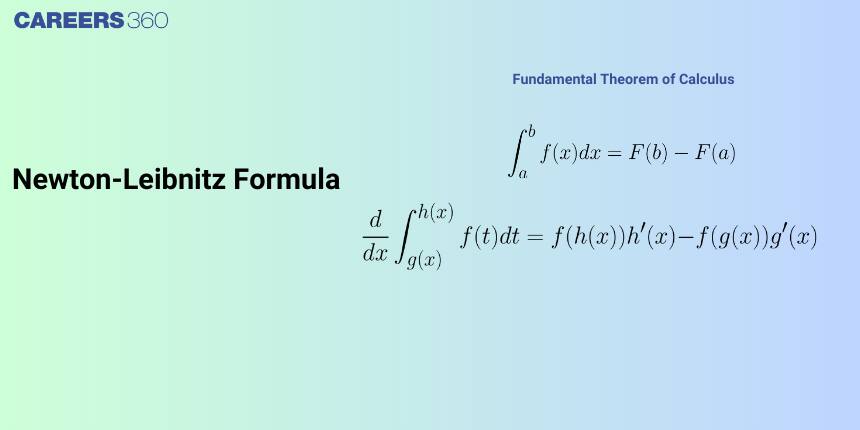

Statement of Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem

If $u(x)$ and $v(x)$ are differentiable functions, and $f(t)$ is continuous on the interval between them, then

$\frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_{u(x)}^{v(x)} f(t)\,dt\right] = f(v(x)) \cdot \frac{d}{dx}(v(x)) - f(u(x)) \cdot \frac{d}{dx}(u(x))$

This formula tells you how to differentiate a definite integral when both the upper and lower limits depend on $x$.

Why This Formula Matters

It works only for definite integrals.

It helps find $\frac{d}{dx}$ of integrals where the variable does not appear inside the integrand but appears in the limits.

It is used frequently in JEE, engineering math, physics, and modelling problems where boundaries change with time or position.

Whenever the limits “move,” the total accumulated value changes, and Newton–Leibniz quantifies that change beautifully.

Review of Basic Definite Integral Concept

If $f(x)$ is continuous on $[a, b]$ and $F(x)$ is an antiderivative of $f(x)$:

$\int_a^b f(x)\, dx = F(b) - F(a)$

Here, $a$ is the lower limit and $b$ is the upper limit.

Proof of Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem (Step-by-Step)

Let $\frac{d}{dx}[F(x)] = f(x)$

Then:

$\int_{u(x)}^{v(x)} f(t)\,dt = F(v(x)) - F(u(x))$

Differentiate both sides:

$\frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_{u(x)}^{v(x)} f(t)\,dt\right] = \frac{d}{dx}[F(v(x)) - F(u(x))]$

Apply chain rule:

$\frac{d}{dx}[F(v(x))] = F'(v(x)) \cdot v'(x)$,

$\frac{d}{dx}[F(u(x))] = F'(u(x)) \cdot u'(x)$

Replace $F'$ with $f$:

$\frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_{u(x)}^{v(x)} f(t)\,dt\right] = f(v(x))\,v'(x) - f(u(x))\,u'(x)$

Alternate Form (When Variable Is $t$)

If limits are $f(t)$ and $\phi(t)$, then

$\frac{d}{dt}\left[\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t)} F(x)\,dx\right] = F(\phi(t))\,\phi'(t) - F(f(t))\,f'(t)$

Special Cases of Newton–Leibniz’s Theorem

Explore specific scenarios where the Newton–Leibniz theorem simplifies integral evaluation, including constant limits, variable limits, and integrands dependent on the integration variable. These special cases extend the theorem's utility in diverse calculus problems and real-world applications.

Case 1: Only Upper Limit Depends on $x$

If the integral is $ \int_a^{g(x)} f(t),dt $, then $ \frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_a^{g(x)} f(t),dt\right] = f(g(x)) \cdot g'(x) $.

This result is extremely helpful when the upper limit of a definite integral depends on $x$, because the derivative simply becomes the integrand evaluated at the boundary multiplied by the derivative of that boundary.

Case 2: Only Lower Limit Depends on $x$

If the integral is $\int_{h(x)}^a f(t)\,dt$, then $\frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_{h(x)}^a f(t)\,dt\right] = -f(h(x)) \cdot h'(x)$

The negative sign comes from reversing limits.

Case 3: Both Limits Are Functions but One Is Constant

If one limit doesn’t change, the corresponding term simply vanishes.

Applications of Newton–Leibniz’s Formula

The Newton–Leibniz Formula plays a crucial role in calculus for evaluating definite integrals using antiderivatives. Its applications span solving integration problems, finding areas, computing derivatives of integrals with variable limits, and proving key results in physics, engineering, and mathematical analysis.

1. Finding Derivatives of Area Functions

If $A(x) = \int_0^{x^2} \sin t\,dt$ ,then

$A'(x) = \sin(x^2) \cdot 2x$

A very common JEE-style problem.

2. Physics Applications: Motion with Moving Boundaries

Examples:

Pressure change across a moving piston

Charge accumulated in a coil as boundary moves

Heat flow across a rod with expanding ends

All these scenarios use the same essential idea — varying limits.

3. Evaluation of Complicated Derivative Problems

Sometimes, expressions like

$\frac{d}{dx}\left[\int_{\ln x}^{x^3} e^{t^2} \, dt\right]$

which seem impossible, resolve instantly using the theorem:

$= e^{(x^3)^2} \cdot 3x^2 - e^{(\ln x)^2} \cdot \frac{1}{x}$

Reverse Use: Turning Derivatives Into Integrals

This theorem also works “backwards”:

If $\frac{d}{dx}F(x) = f(x)$,

then $F(x) = \int f(x)\,dx$

It establishes the core relationship behind the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

Practical Tips for Using Newton–Leibniz in Exams

Always check whether limits depend on the variable.

Differentiate limits using chain rule.

Replace $F'(x)$ with $f(x)$ at the end.

Watch out for sign errors when limits reverse.

Solved Examples Based on Newton Leibnitz's Theorem

Example 1: Let $F: R \rightarrow R$ be a differentiable function having $f(2)=6, f^{\prime}(2)=\left(\frac{1}{48}\right)$. Then $\lim _{x \rightarrow 2} \int_6^{f(x)} \frac{4 t^3}{x-2} d t$ equals

1) 18

2) 24

3) 36

4) 12

Solution

NEWTON LEIBNITZ THEOREM -

$\frac{d}{d t}\left(\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t))} F(x) d x\right)=F(\phi(t)) \phi^{\prime}(t)-F(f(t)) f^{\prime}(t)$

$f(2)=6 ; f^{\prime}(2)=1 / 48$

$\lim _{x \rightarrow 2} \int_6^{f(x)} \frac{4 t^3 d t}{x-2}=\lim _{x \rightarrow 2} \frac{4(f(x))^3 \times f^{\prime}(x)}{1}$

$\Rightarrow 4(f(2))^3 \times f^{\prime}(2)$

$\Rightarrow 4 \times 6^3 \times \frac{1}{48}=\frac{4 \times 216}{48}=18$

Hence, the answer is the option 1.

Example 2: If $f(x)=\int_0^x t(\sin x-\sin t) d t$

then

1) $f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)+f^{\prime \prime}(x)=\sin x$

2) $f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)+f^{\prime \prime}(x)-f^{\prime}(x)=\cos x$

3) $f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)+f^{\prime}(x)=\cos x-2 x \sin x$

4) $f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)-f^{\prime \prime}(x)=\cos x-2 x \sin x$

Solution

NEWTON LEIBNITZ THEOREM -

$\frac{d}{d t}\left(\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t))} F(x) d x\right)=F(\phi(t)) \phi^{\prime}(t)-F(f(t)) f^{\prime}(t)$

$f(x)=\int_0^x t \sin x d t-\int_0^x t \sin t d t$

$=\frac{x^2}{2} \sin x-\int_0^x t \sin t$

$f^{\prime}(x)=x \sin x+\frac{x^2}{2} \cos x-x \sin x$

$f^{\prime}(x)=\frac{x^2}{2} \cos x$

$f^{\prime \prime}(x)=x \cos x-\frac{x^2}{2} \sin x$

$f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)=-x \sin x+\cos x-x \sin x-\frac{x^2}{2} \cos x$

Thus $f^{\prime \prime \prime}(x)+f^{\prime}(x)=\cos x-2 x \sin x$

Hence, the answer is the option 3.

Example 3: Let $f:(0, \infty) \rightarrow R$ and $F(x)=\int_1^x f(t) d t$. If $F\left(x^2\right)=x^2(1+x)$ then $f(4)$ equals :

1) 5/4

2) 7

3) 4

4) 2

Solution

NEWTON LEIBNITZ THEOREM -

$\frac{d}{d t}\left(\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t))} F(x) d x\right)=F(\phi(t)) \phi^{\prime}(t)-F(f(t)) f^{\prime}(t)$

$F^{\prime}(x)=f(x)$

$F(x)=x(1+\sqrt{x})=x+x^{\frac{3}{2}}$

$F^{\prime}(x)=f(x)=1+\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{x}$

$\therefore f(4)=4$

Hence, the answer is the option (3).

Example 4: $\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\int_0^{x^2} \cos t^2 d t}{x \sin x}=?$ :

1) 1

2) 2

3) 0

4) 0.5

Solution

NEWTON LEIBNITZ THEOREM -

$\frac{d}{d t}\left(\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t))} F(x) d x\right)=F(\phi(t)) \phi^{\prime}(t)-F(f(t)) f^{\prime}(t)$

Limit= $\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\frac{d}{d x} \int_0^{x^2} \cos t^2 d t}{\frac{d}{d x}(x \sin x)}=\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\cos \left(x^2\right)^2 \cdot \frac{d\left(x^2\right)}{d x}}{\sin x+x \cos x}$

$=\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{2 x \cos x^4}{\sin x+x \cos x}=\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{2 x \cos x^4}{x \cdot\left(\frac{\sin x}{x}\right)+x \cos x}=\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{2 \cos x^4}{1+\cos x}=1$

Hence, the answer is the option (1).

Example 5: if $\int_{\sin x}^1 t^2 f(t) d t=1-\sin x, x \in\left(0, \frac{\Pi}{2}\right)$ then $f\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)=$ :

1) 3

2) $\frac{1}{3}$

3) $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$

4) $\sqrt{3}$

Solution

NEWTON LEIBNITZ THEOREM -

$\frac{d}{d t}\left(\int_{f(t)}^{\phi(t))} F(x) d x\right)=F(\phi(t)) \phi^{\prime}(t)-F(f(t)) f^{\prime}(t)$

On differentiating both sides, we get

$\Rightarrow-\sin ^2 x f(\sin x) \cos x=-\cos x$

$\begin{aligned} & \Rightarrow f(\sin x)=\operatorname{cosec}^2 x \\ & \Rightarrow f(x)=\frac{1}{x^2} \\ & \Rightarrow f\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)=3\end{aligned}$

Hence, the answer is the option (1).

List of Topics Related to Newton-Leibnitz's Formula

This section covers key topics connected to Newton-Leibnitz's Formula, including applications of integrals, integrals of particular functions, indefinite integrals, integration by parts, and the application of inequalities in definite integration. These topics provide a thorough foundation for understanding and applying the fundamental theorem of calculus efficiently.

Integral of Particular Functions

NCERT Resources

Access comprehensive NCERT resources for Class 12 Maths Chapter 7 on Integrals, including detailed notes, complete solutions, and exemplar problem sets. These materials are expertly prepared to aid concept clarity and boost exam preparation.

NCERT Class 12 Maths Notes for Chapter 7 - Integrals

NCERT Class 12 Maths Solutions for Chapter 7 - Integrals

NCERT Class 12 Maths Exemplar Solutions for Chapter 7 - Integrals

Practice Questions based on Newton-Leibnitz's Formula

Test your understanding of Newton-Leibnitz's Formula with these targeted MCQs designed to sharpen your calculus skills. Practice problems cover key concepts and applications essential for exam success, especially in JEE Main and other competitive exams.

Newton Leibnitzs Formula- Practice Question MCQ

We have provided below the practice questions related to different concepts of integration to improve your understanding:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

It applies mainly to proper integrals; improper ones require limit evaluation for infinite or discontinuous bounds.

For variable limits, the Leibnitz rule generalizes the formula and involves differentiating the integral with respect to $x$ using the chain rule.

Find the antiderivative $F(x)$ of the integrand $f(x)$, then compute the difference $F(b) - F(a)$ for the limits $a$ to $b$.

It provides a method to evaluate definite integrals by finding an antiderivative, simplifying the computation of areas under curves.

Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz independently formulated this fundamental theorem of calculus connecting differentiation and integration.