Electron Configuration - Meaning, Definition, Rules, Table, FAQs

Why do elements show different chemical properties despite being made of the same fundamental particles? How are electrons arranged around the nucleus of an atom, and what rules govern their distribution in various energy levels and orbitals? The answers to all these questions lie in the electronic configuration of atoms. Understanding how electrons are written, filled, and represented in atomic orbitals helps explain the periodic trends, valency, bonding behavior, and reactivity of elements.

This Story also Contains

- Electronic Configuration

- Rules for Writing Electronic Configuration

- Rules for filling orbitals in Electron Configuration

- Representation of Electronic Configuration of an Atom

- Noble Gas Electron Configuration

- Some Solved Examples

Electronic Configuration

Electronic configuration is the systematic arrangement of electrons of an atom in different energy levels (shells), subshells, and atomic orbitals around the nucleus. It describes how electrons are distributed in an atom according to increasing energy and specific filling rules.

Electronic configuration helps in understanding the chemical properties, valency, bonding nature, stability, and periodic behavior of elements.

Rules for Writing Electronic Configuration

The electronic configuration of an atom refers to the systematic arrangement of electrons in various energy levels and orbitals around the nucleus. Writing electronic configurations helps us understand the chemical behavior, valency, bonding nature, and periodic trends of elements.

Electrons are distributed in shells and subshells based on increasing energy. Each shell is designated by a principal quantum number (n = 1, 2, 3, …) and contains subshells such as s, p, d, and f. While writing electron configurations, electrons are filled in orbitals in such a way that the total energy of the atom remains minimum.

For example:

-

Electronic configuration of Hydrogen (Z = 1) $\rightarrow 1 \mathrm{~s}^1$

-

Electronic configuration of Oxygen (Z = 8) $\rightarrow 1 \mathrm{~s}^2 2 \mathrm{~s}^2 2 \mathrm{p}^4$

Rules for filling orbitals in Electron Configuration

-

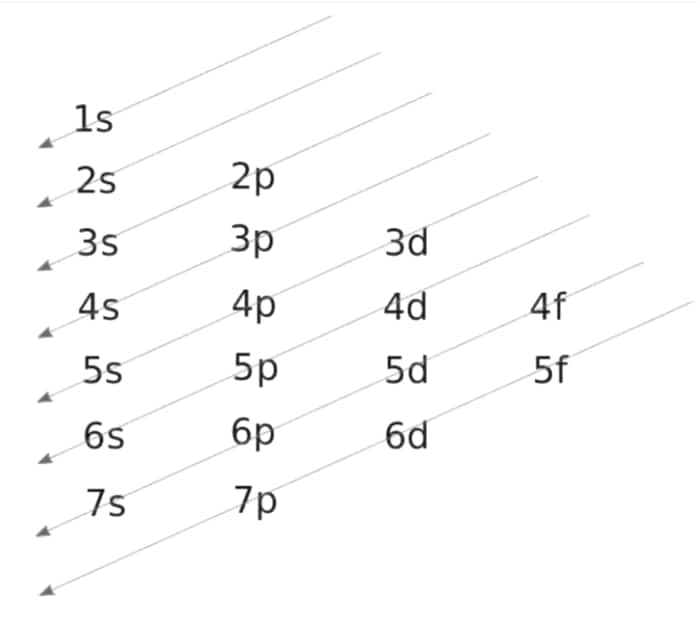

Aufbau Rule: The term "Aufbeen" comes from the German word "aufbauen," which means "to build up." According to the Aufbau principle, electrons will first occupy lower-energy orbitals before moving on to higher-energy orbitals. The sum of the primary and azimuthal quantum numbers is used to compute the energy of an orbital. Electrons are filled in the following order according to this principle: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p.

It's worth noting that the Aufbau principle has many exceptions, such as chromium and copper. The stability afforded by half-full or entirely filled subshell electronic configurations can occasionally explain these exceptions.

-

Pauli exclusion principle: According to the Pauli exclusion principle, an orbital can only hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins. “No two electrons in the same atom have the same values for all four quantum numbers,” says this principle. As a result, if two electrons have the same primary, azimuthal, and magnetic numbers, they must have opposite spins.

-

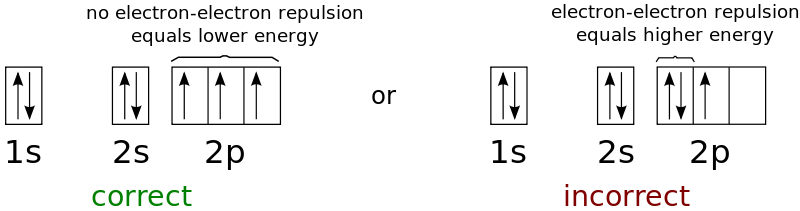

Hund’s Rule: This rule specifies the order in which electrons are filled in all of a subshell's orbitals. It asserts that before a second electron is inserted in an orbital, every orbital in a particular subshell is single-occupied by electrons. The electrons in orbitals with only one electron have the same spin in order to maximise the total spin (or the same values of the spin quantum number).

Example: the electronic configuration is $1 s^2 2 s^2 2 p^3$, it can be represented using hund’s rule as:

Related Topics link

Representation of Electronic Configuration of an Atom

Electronic configuration can be represented in different ways depending on the requirement:

1. Orbital Notation

In this method, each orbital is represented by a box and electrons by arrows $(\uparrow \downarrow)$, showing their spins.

Example for Nitrogen (Z = 7): $1 s^2 2 s^2 2 p^3$

Here, the three 2p electrons occupy separate orbitals with parallel spins.

2. Shell-wise Representation

Electrons are distributed among shells as K, L, M, N.

Example:

-

Sodium $(Z=11) \rightarrow 2,8,1$

3. Noble Gas Configuration

To simplify writing, the configuration of the nearest noble gas is used as a core.

Example:

-

Chlorine $(Z=17) \rightarrow[N e] 3 s^2 3 p^5$

This method is especially useful for writing configurations of transition and inner-transition elements.

Related Topics link

Noble Gas Electron Configuration

|

Element |

Electronic configuration |

|

Helium | $1 \mathrm{~s}^2$ |

|

Neon | $[\mathrm{He}] 2 s^2 2 p^6$ |

|

Argon | $[\mathrm{Ne}] 3 s^2 3 p^6$ |

|

Krypton |

$[A r] 3 d^{10} 4 s^2 4 p^6$ |

|

Xenon | $[\mathrm{Kr}] 4 d^{10} 5 s^2 5 p^6$ |

|

Radon | $[\mathrm{Xe}] 4 f^{14} 5 d^{10} 6 s^2 6 p^6$ |

|

Oganesson |

[$[R n] 5 f^{14} 6 d^{10} 7 s^2 7 p^6$ |

Also check-

Some Solved Examples

Question 1: Which of the following is electronic configration of Li ?

1) (correct) $1 \mathrm{~s}^2 2 \mathrm{~s}^1$

2) $1 s^2 2 s^2$

3) $1 s^1 2 s^1$

4) $1 \mathrm{~s}^1$

Solution:

As we have learnt-

Atomic number of Li is three.

Li : 1s22s1

Hence, the answer is the option (1).

Question 2: The electronic configuration of Einsteinium is: (Given atomic number of Einsteinium $=99$ )

1) $[\mathrm{Rn}] 5 \mathrm{f}^{12} 6 \mathrm{~d}^0 7 \mathrm{~s}^2$

2) (correct) $[\mathrm{Rn}] 5 \mathrm{f}^{11} 6 \mathrm{~d}^0 7 \mathrm{~s}^2$

3) $[\mathrm{Rn}] 5 \mathrm{f}^{13} 6 \mathrm{~d}^0 7 \mathrm{~s}^2$

4) $[\mathrm{Rn}] 5 \mathrm{f}^{10} 6 \mathrm{~d}^0 7 \mathrm{~s}^2$

Solution:

Einsteinium (atomic $\mathrm{No}=99$ ) : $[R n] 5 \mathrm{f}^{11} 6 \mathrm{~d}^0 7 \mathrm{~s}^2$

Hence, the answer is the option (2)

Question 3: The total number of species from the following in which one unpaired electron is present, is $\_\_\_\_$ .

$\mathrm{N}_2, \mathrm{O}_2, \mathrm{C}_2^{-}, \mathrm{O}_2^{-}, \mathrm{O}_2^{2-}, \mathrm{H}_2^{+}, \mathrm{CN}^{-}, \mathrm{He}_2^{+}$

Solution:

One unpaired $\mathrm{e}^{-}$is present in : $\mathrm{C}_2^{-} ; \mathrm{O}_2^{-} ; \mathrm{H}_2^{+} ; \mathrm{He}_2^{+}$

Hence, the answer is (4).

Question 4: The electronic configuration of an element is $1 s^2 2 s^2 2 p^6 3 s^2 3 p^6 3 d^5 4 s^1$ This represents its:

1) Excited state

2) (correct) Ground state

3) Cationic form

4) Anionic form

Solution:

Ground state, because half-filled d - orbital is more stable.

Hence, the answer is the option (2).

Practice more question with link given below

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Copper has the electronic configuration of atoms[Ar]3d104s1. Due to the narrow energy gap between the 3d and 4s orbitals, this electronic structure violates the aufbau principle. The fully filled d-orbital arrangement is more stable than the partially filled one.

These are the orbitals which tells us about the order and number of electrons in each shell. The maximum number of electrons that can fill in these orbitals are:

s: 1 orbital, 2 electrons.

p: 3 orbitals, 6 electrons.

d: 5 orbitals, 10 electrons.

f: 7 orbitals, 14 electrons.

The electron configuration of an atom can be used to calculate the number of valence electrons present. The orbitals associated with an atom's highest occupied energy level include valence electrons. The remaining electrons, known as inner shell electrons, aren't involved in bonding. Example- the electronic configuration of sulphur is :

S=1s22s22p63s23p4 Sulphur has its electrons in 3 energy levels, valence electrons are the outermost electron thus found in the highest energy shell occupied. As a result, only electrons associated with an energy level/orbital combination that starts with a 3 must be examined in this scenario. Both orbitals are chosen for further analysis because two energy level/orbital pairings begin with a 3:

3s23p4

There are a total of six superscripts linked with these orbitals. Sulfur contains six valence electrons as a result.

Electronic Configuration is the dispersion of electrons in an atom. The formula 2n2, where n=orbit number, aids in determining the maximum number of electrons present in an orbit. The formula is known as the "Bohr Bury Schemes," and it aids in the determination of electron configuration.

By assisting in the determination of an atom's valence electrons, electron configurations provide insight into the chemical behaviour of elements. It also aids in the classification of elements into separate blocks (such as the s-block elements, the p-block elements, the d-block elements, and the f-block elements). This makes it easy to investigate the properties of the components as a group.